Parallel Construction: The DEA Once “Stole” a Dealer's Car

This is an old tale of how the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration used parallel construction to arrest a drug trafficker after secretly intercepting his phone calls.

Introduction

The United States Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) was investigating a drug trafficking gang in the early 2000s and wanted to arrest a member of the gang named Ascension Alverez-Tejeda. The DEA had conducted some traditional investigative tactics, such as physical surveillance. Through these methods, the DEA had identified Alverez-Tejeda as a person of interest. The real information that led to the defendant’s arrest stemmed from intercepted phone calls. The DEA needed a way to arrest the defendant in a way that kept the source of the information out of the courtroom.

Special Operations Division aka Dark Side

The DEA has a Special Operations Division (SOD) that, along with other federal investigative agencies, receives raw communication data from the National Security Agency’s mass surveillance programs. Documents released by Edward Snowden revealed that the DEA, through the SOD, has a good working relationship with the NSA. In 2015, it was revealed that the DEA had “amassed logs of virtually all telephone calls from the USA to as many as 116 countries linked to drug trafficking." The way the SOD works allows the division to pass on information to other agents who do not receive information about the legality of the information or the source, etc.

A Special Operations Division badge shown to a Human Rights Watch researcher. Yes, that is Darth Vader. | HRW

Hemisphere

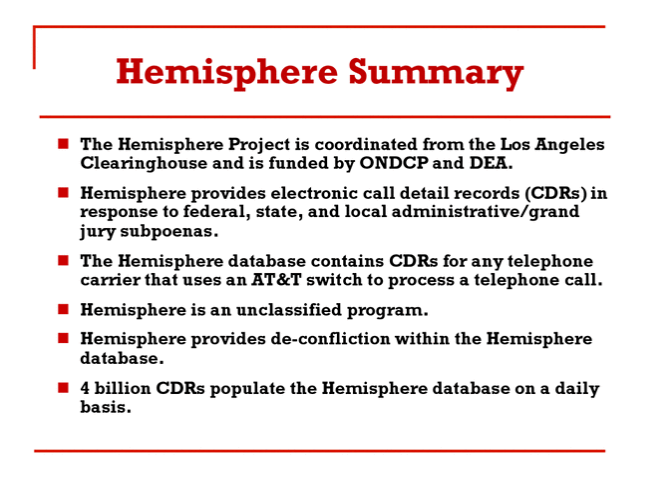

It is an established fact that the DEA has been collecting call records at a scale that dwarfs even the NSA. For example, slides released in 2013 detailed a DEA program called Hemisphere.

NYT:

The scale and longevity of the data storage appears to be unmatched by other government programs, including the N.S.A.’s gathering of phone call logs under the Patriot Act. The N.S.A. stores the data for nearly all calls in the United States, including phone numbers and time and duration of calls, for five years.

Hemisphere covers every call that passes through an AT&T switch — not just those made by AT&T customers — and includes calls dating back 26 years, according to Hemisphere training slides bearing the logo of the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy. Some four billion call records are added to the database every day, the slides say; technical specialists say a single call may generate more than one record. Unlike the N.S.A. data, the Hemisphere data includes information on the locations of callers.

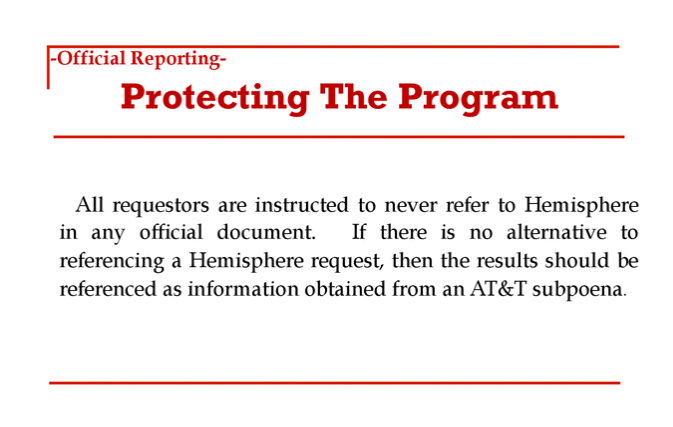

A government presentation indicated that agents could issue subpoenas to re-obtain any call records they originally found through Hemisphere, thus preventing the program from being disclosed.

Parallel Construction

Investigators received a major break in the case after obtaining call records pertaining to Alverez-Tejeda’s criminal activities (it is unlikely the DEA obtained the logs through the Hemisphere program but the operation is a fit for the DEA’s SOD).

After receiving information from the call logs about Alverez-Tejeda, the DEA needed a way to act on that data while completely concealing the source of their information. This act, as we all know, is described as parallel construction. The result of their parallel construction in this case, which a judge has called a “ruse” with the “potential to spin out of control and exceed reasonable bounds,” might set the bar for the most dramatic scenario created by federal law enforcement officers.

The DEA had learned about Alverez-Tejeda’s plans after accessing the call records. Specifically, the information revealed that Alverez-Tejeda would be traveling from Los Angeles to Washington with an assortment of drugs in the car, including methamphetamine and cocaine. (The Intercept reported that Alverez-Tejeda would be using his car. The Ninth Circuit Court stated that the car belonged to one Jose Luis Carrillo-Mendez.)

The DEA’s “ruse”

The DEA, being the federal drug police, needed to arrest Alverez-Tejeda; undercover agents had previously purchased drugs from someone in the same vehicle but Alverez-Tejeda was not present.

So, in order to construct a parallel narrative, the DEA essentially functioned as actors in a skit that resembled a fever dream.

First, they had one agent in a car in front of Alverez-Tejeda’s car. They had another agent in a truck behind Alverez-Tejeda’s. After a stoplight turned green, the agent in front of Alverez-Tejeda accelerated briefly before stomping on the brakes. Alverez-Tejeda did the same thing. The DEA agent behind him, though, rear-ended Alverez-Tejeda’s vehicle.

In no time, the police had arrived at the scene of the accident and determined that the driver of the truck behind Alverez-Tejeda had been under the influence. They “arrested” the agent and got him off the stage. Police then convinced Alverez-Tejeda (and his apparently innocent girlfriend who was with him during the trip) to drive their car to a nearby parking lot. Police told Alverez-Tejeda to leave his keys in the car and then to sit in the back of a nearby police car (with his girlfriend) until an officer could come to take their statements about the accident.

While sitting in the police car, an apparent car thief (hint: the thief the DEA) hopped in Alverez-Tejeda’s car and drove off. The police ordered Alverez-Tejeda and his girlfriend out of the cruiser and then took off in pursuit of the car. Moments later, the defendant watched his car drive past the same parking lot with the cruiser in hot pursuit.

The police officer later returned with only a purse the carjacker had apparently thrown out the window while driving. The purse belonged to Alverez-Tejeda’s girlfriend. The police put the couple up in a nearby hotel until they could resolve the issue (which presumably means return the car but we all know that is not an overnight process). Later, once the police “caught” the “carjacker,” they obtained a warrant from a judge that allowed them to search the car. They obviously failed to disclose any of the details of their ruse. During the search, the police found methamphetamine and cocaine.

Fourth Amendment Violation Appeal

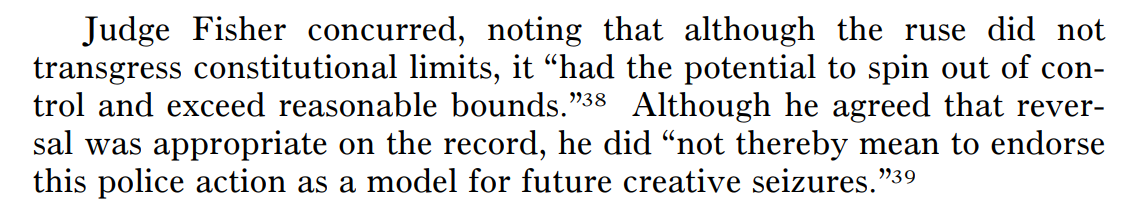

The government indicted Alverez-Tejeda on drug charges for the methamphetamine and cocaine found in his car. Later, a judge in the District Court of Washington ruled that the DEA’s ruse had violated the Fourth Amendment (which is designed to protect people from unreasonable searches and seizures conducted by agents of the government). The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals overturned the ruling from the lower court. The Appeals Court ruled that law enforcement already had probable cause to search the car after arresting the “carjacker” and that the DEA’s parallel construction caper had not crossed any lines (not. even. state. lines.).

The government here certainly had important reasons for employing this unusual procedure in seizing the car. First, the agents wanted to stop the drugs before they reached their ultimate destination – a patently important goal. Second, they wanted to protect the anonymity of the ongoing investigation – another vital objective.

Judge Raymond Fischer, while agreeing with his colleagues, wrote that the DEA’s unconventional search had “pushed the envelope” and “had the potential to spin out of control and exceed reasonable bounds.”

Although many of you (and perhaps most) already know this story, I figured it would be an interesting look into the lengths the feds will go to in an attempt to catch you. These tactics are interesting (to me at least) and in some cases are just hard to fathom.